Calling All Robots

At first glance, A-UGVs (autonomous unmanned ground vehicles) may not seem to have much in common with other 21st century technologies like additive manufacturing (AM) and smart infrastructure. Look closer, however, and you begin to see common threads: use of machine-learning concepts, reliance on automated systems, and digital interconnectivity, to name

a few.

As of fall 2021, these efforts will share something else: an expanded ASTM International committee. The committee will enable stakeholders representing a variety of industries to work together on areas where their disciplines overlap.

The newly reconstituted committee on robotics, automation, and autonomous systems (F45) also marks a new phase in ASTM’s ongoing efforts to carry out its mission in a more holistic way, and thus enhance its value to members and industry partners. The story of the new F45 is really a story about technological innovations in manufacturing, particularly the convergence of adjacent emerging technologies digitally within a physical infrastructure and system. These manufacturing innovations are creating opportunities for the coordination of standards development that will benefit all who participate.

READ MORE: Autonomous Vehicles Move Forward

The Right Moment

Many ASTM committees have been organized on specific materials or product categories. From the organization’s earliest days, when engineers, business owners, and other concerned stakeholders came together to develop standards for steel used in railroad tracks and bridge structures, committees have often focused on their particular niche (while addressing a wide range of issues within those niches).

Committee F45, in its original incarnation, was no different. Formed seven years ago in response to the increasing use of driverless vehicles and autonomous mobile robots in manufacturing, warehouse, and delivery applications, the group has since taken a leading role in standards related to measurement of A-UGV performance. The first was terminology (F3200), which has helped facilitate communication in the industry since its publication in 2016.

Other accomplishments include development of a standard practice for describing stationary objects utilized within A-UGV test methods (F3381), and of test methods for navigation in a confined area (F3244), grid-video obstacle measurement (F3265), and confirming A-UGV docking performance (F3499). The committee has so far published nine standards, with others underway.

Now, however, F45 will cast a much wider net. Roger Bostelman, Ph.D., has been committee chair since its inception, and he is a research associate in the Intelligent Systems Division of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). As he recounts, those involved in the committee’s formation realized that A-UGVs were just the tip of the iceberg even before it was officially launched.

“Prior to the formation of F45, NIST discussed with ASTM the need for several standards committees in the robotics realm, dealing not only with autonomous vehicles but also robot performance, mobile manipulators (robot arms onboard autonomous vehicles), grasping, perception, and other areas,” Bostelman says. “The intention was always there. We were just waiting for the most appropriate time to do so.”

It turns out 2021 is that time.

The Logical Spot

“We wouldn’t be doing this if we didn’t see a need, and if we didn’t see a way for ASTM to use what we’re really good at to help contribute to solving some of the challenges that are out there.”

These are the words of Leonard Morrissey, ASTM’s director of global business development and strategy, who has been very involved in the work to expand F45’s scope of activities. He explains that while it’s the members who usually determine the direction in which their committees evolve, in the case of F45, his team’s higher-level landscape analysis helped shape the process.

“If you’re focused on your industry sector, what you’re supposed to be doing is developing solutions for your industry sector. From our business-development perspective, however, we need to see how all these individual ‘tribes’ marry up and see if there’s a broader, universal way to address these issues,” he says.

Arriving at a new name for F45 may not seem like a big deal, but it was actually an important first step. “By calling it certain things, you’re by default excluding things you don’t mean to exclude, and these concepts, these terms, change all the time,” Morrissey points out. “So it has been a challenge, but we’ve got great people who are engaged, and that’s the beauty of the ASTM process, that we have necessarily disparate perspectives.”

The consensus pick for the new name — the committee on robotics, automation, and autonomous systems — perfectly reflects F45’s new direction. And while the structure of the committee is still being worked out, early recommendations feature dedicated sections for topics like smart infrastructure, logistics, sensors, advanced manufacturing, cybersecurity, and of course, A-UGVs.

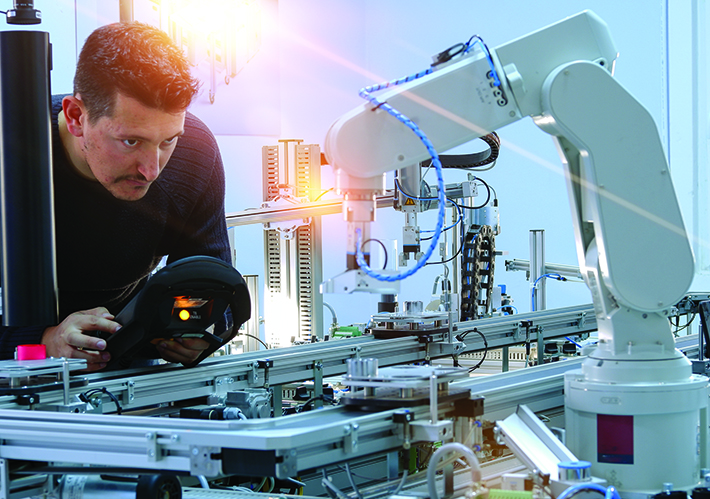

Robots have gone from the realm of science fiction to making daily life more efficient and productive.

A September workshop was designed to give industry stakeholders the opportunity to come forward and help ASTM define the specific standards they want to see developed. The hope is that some of these individuals will become committee officers. A new chair will also be needed as, per ASTM regulations, Roger Bostelman must relinquish his post at the end of this year.

Striking a NERVE

Committee secretary Adam Norton also believes the committee is the logical launch pad for a more comprehensive assessment of the standards that will be required in different segments of advanced manufacturing. “The primary domain where F45 A-UGV standards are applicable is in manufacturing, which is rife with other types of robotic systems and automation like manipulators, sensors, and other smart infrastructure,” he says.

Norton is assistant director of the New England Robotics Validation and Experimentation (NERVE) Center at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, and is also working with ASTM’s Exo Technology Center of Excellence (ET CoE) on research to standards work. NERVE has collaborated with several ASTM committees, including the committees on exoskeletons and exosuits (F48) and homeland security applications (E54), conducting valuable research that has helped propel new standards forward in these areas.

The center also works with F45. For example, NERVE researchers were instrumental in developing the test methods for evaluating navigation and obstacle avoidance that were incorporated as a revision to F3244 (the test method for navigation: defined area), which passed in May. The new committee will rely on NERVE and other partners in academia for support as it expands its scope, something Norton sees as an excellent opportunity for synergy.

“The NERVE Center develops test methods and metrics for many different robot domains,” he explains. “One of the most prominent is robotic manipulation. Our robotic manipulator testbed, the ARMada, consists of a variety of dual-armed and single-armed robot systems designed to be used interchangeably with a series of end effectors and sensors. The expansion of our committee to include manipulators will enable NERVE to further contribute to this area.”

Norton cites grasping and manipulation as promising areas for robotics research, and he notes that many of the commonly used benchmarks and test methods in this segment have yet to be standardized. “There is a very clear path forward for these areas in F45. For example, evaluating the characteristics of an end effector (grasp strength, cycle time, finger strength), comparison of grasping algorithms on a common task, and standard measurements of pick and place activities, to name a few.”

Adjacent Technologies and Research

According to Bostelman, one important aspect of the committee’s new agenda will be to identify and fill standards gaps within ASTM. “For example, the committee on 3D imaging systems (E57) develops perception standards but perhaps doesn’t address perception from an autonomous vehicle or mobile manipulator perspective when used for obstacle avoidance or human detection,” he says. The new F45 will be able to address that perspective.

Another exciting prospect is the potential for collaboration with ASTM’s two Centers of Excellence. William Billotte, Ph.D., director of global exo technology programs with ASTM, is convinced that F45 and the ET CoE, which he heads, will complement each other very well.

“Exoskeletons may utilize robotic components and semi-autonomous systems as well as incorporate sensors,” he says, adding that they may also be utilized in advanced manufacturing and logistics workplaces. “Thus, the members of F45 will be developing standards that help the safety and reliability of exo technologies.”

Data security is a particular concern as the Internet of Things (IOT) and other forms of digital connectivity proliferate. Billotte suggests that as the manufacturing environment moves toward a more human-centric framework, it will be critical for F45 to address this issue.

“Standards will have to be robust enough to enable this framework, where these systems will surround, cue from, and interface with the worker through exoskeletons and other wearables,” Billotte says. “Therefore, secure data and communications are a critical component of this, as accuracy and quality of data not only enable productivity but are paramount to safety for the worker.”

Billotte highlights a current work item within the exoskeleton/exosuits committee — effective cybersecurity management for exoskeletons (WK76659) — as an example of a proposed standard that may benefit from F45’s new focus on data formats and communications. “I’m hopeful that these two committees will leverage each other’s expertise and develop standards that are stronger because of these synergies,” he says.

As the leader of ASTM’s Additive Manufacturing Center of Excellence (AM CoE) and director of global additive manufacturing programs for ASTM, Mohsen Seifi, Ph.D., is also optimistic regarding advances that could be realized through the coordinated efforts of the AM CoE and F45. For instance, he sees strong potential in the area of automation of post processes after a build is complete.

“One example is to automate the unpacking of a complete build to improve de-powdering efficiency for powder-bed fusion processes followed by wire cutting,” Seifi says. “Often, the machines responsible for each task are from different manufacturers, and machine-to-machine communication can be a challenge. To achieve a seamless transition from feedstock preparation to post-processing, the machines need to rely on a common communication protocol for data transfer. This is crucial for the factories of the future, where robots will conduct much of the work.”

Seifi also points to ongoing research carried out by the Centers of Excellence, noting its importance to the work of committees like F45. Billotte echoes this view.

FOR YOU: Taking a Bite Out of Cybercrime

“One of the ways we pursue the goal of safe and reliable exo technologies is through acceleration of standards by funding targeted research projects in priority areas for the exo community. We often refer to this as research to standards, or R2S,” Billotte explains. “I am hoping that the new F45 identifies areas that need such research.”

Evidence of the success of this approach is compelling. “We have demonstrated over the past three years that conducting targeted R&D can significantly accelerate and improve the development of standards,” Seifi notes. “The results and data generated from R&D projects can lead to new standards being developed and contribute to the revision of existing standards.”

Roadmap to the Future

The expansion of the F45 committee opens up a new world of possibilities for standards that could impact a wide range of advanced manufacturing operations. It also represents an interesting milestone in the evolution of ASTM and its mission.

“I think it’s going to be very infrequent that you’re seeing issues only related to one particular industry silo anymore,” says Morrissey. He mentions the committee on sustainability (E60) as a successful example of an “overarching” committee — similar to the new F45 — that examines how this critical topic applies to different industries, mainly in the building sector.

And it’s not just about standards. “Standards are ASTM’s bread and butter, they’re what we do, but educational workforce development is also necessary for these things,” Morrissey notes.

“The certification, the quality assurance, the advisory services where needed — ASTM is a big machine with a lot of tools in its tool belt, and we’re trying to see if we can be smarter about how we leverage that.”

Morrissey anticipates a kind of modular approach where, as more is learned, additional areas that need to be addressed will emerge. “I see this blossoming out like a spider web,” he says. “Not only developing the standards and the guidance but also the coordination.”

Take the committee on consumer products (F15). “They have a standard on the safety of connected products, IOT, which from a safety perspective is well within what they should be doing,” Morrissey explains. “But how does that apply to sensor technologies and smart technologies in the pedestrian/walkway safety and footwear committee (F13)? We want to have somebody at the next level up saying ‘OK, how can we learn from those practices, how can we adapt them to other areas?’”

One thing that won’t change is ASTM’s reliance on industry stakeholders to identify the areas they see as needing some form of standardization. Between the September workshop and the upcoming full committee meetings in October, it is hoped that an influx of new volunteers will step forward to help lead the committee on robotics, automation, and autonomous systems — both as officers and committee members — as it embarks on an even more collaborative future. ■

Jack Maxwell is a freelance writer based in Westmont, New Jersey.

SN Home

SN Home Archive

Archive Advertisers

Advertisers Masthead

Masthead RateCard

RateCard Subscribe

Subscribe Email Editor

Email Editor