Safer Children’s Costumes

In many countries around the world, it’s that time of year again. Costume makers are unveiling their latest designs, hoping to capture the imagination of young customers. Parents may be planning parties or mapping out the routes they’ll travel with their children in the quest for candy and treats. And the children? They’re champing at the bit to get dressed up and start wielding light sabers.

We’re talking, of course, about Halloween, a holiday celebrated in countries from Mexico to Ireland to Italy. And although the coronavirus pandemic will undoubtedly affect some aspects of this popular global holiday, one thing it probably won’t impact is the desire among girls and boys to stretch their imaginations and transform themselves into fantastical creatures and characters.

As much fun as this yearly spectacle can be, one element of the holiday is extremely serious: safety. Some communities set aside late afternoon hours for trick-or-treating to minimize the risks that come with children darting into the street after dark. Parents often accompany their kids as they make the rounds, and many inspect the goodie bags to make sure everything is safe to eat.

FOR YOU: Safer Toys and Children's Products

And then there are the costumes themselves, which is where ASTM International comes in. One of the standards most widely used to determine the fire resistance of various fabrics is the test method for flammability of apparel textiles (D1230). Developed by the committee on textiles (D13) and last updated in 2017, this standard is currently being reviewed and revised to reflect new developments in the industry and to align it with CPSC’s update to the mandatory regulation.

The Flammable Fabrics Act

The history of apparel flammability standards in the United States dates to 1953, when Congress enacted the Flammable Fabrics Act or FFA. The legislation specified that a test be used to determine if fabric or clothing is ”so highly flammable as to be dangerous when worn by individuals.”

Enforcement of the statute initially fell under the purview of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission but was transferred to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) with its creation in 1972. This shift gave the CPSC the power to issue and amend mandatory flammability standards, including apparel flammability standards. In 1975, the commission codified the standard for the flammability of clothing textiles into federal law as 16 CFR Part 1610. Its efficacy is reflected in the fact that it is the basis for ASTM D1230 and cited in other countries’ regulations as a basis for flammability screening of textiles.

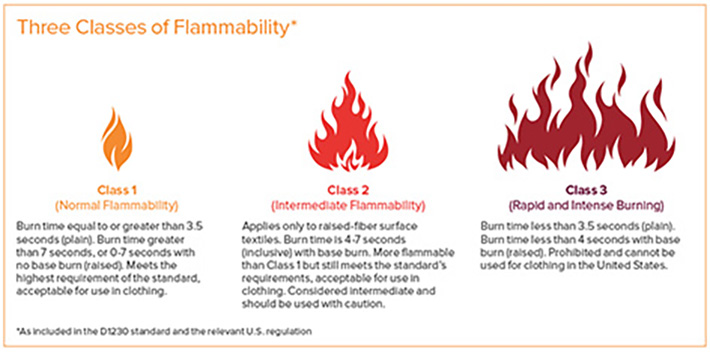

This standard, referred to simply as “1610” in the industry, includes a description of the apparatus that must to be used and the procedures that must be followed to test textiles intended for use in clothing as well as finished clothing items. It also distinguishes between two basic types of fabrics — plain surface and raised (i.e., napped) surface — and establishes three classes of flammability (see sidebar).

Ellen Roaldi, chairman of the subcommittee on flammability (D13.52) and a senior global technical consulting specialist at Bureau Veritas, emphasizes the importance of this type of testing. “It is an effective tool for weeding out dangerously flammable fabrics,” she says.

Passing the Test

Most fabrics are inherently susceptible to fire. However, variables such as fiber content, weight, construction, and finishing determine the degree to which a particular fabric is flammable, what could happen when it is ignited, and how fast it will burn. Testing is necessary to observe and quantify how these different characteristics of a fabric affect its performance when exposed to an open flame, as well as determine fabrics suitable for use in clothing.

The first test used to assess a clothing item’s resistance to flame was called the flammability of clothing textiles, commercial standard (191-53), and was specified in the original FFA legislation. The procedures used became part of federal law in 1975 as 16 CFR Part 1610 and were last updated in 2008.

The test itself is conducted with five 50 x 150 mm (2 x 6 inch) fabric specimens, which must be tested twice: first in their original state and then after what is referred to as “refurbishing,” which is essentially dry cleaning and laundering. The specimens are evaluated in a special flammability test chamber that is draft-proof, ventilated, and equipped with a rack to hold them at a 45-degree angle. Flame is applied to the surface near the lower edge of the fabric for one second, and the time it takes for the flame to spread 127 mm (5 inches) up the sample is recorded.

Results are determined by averaging the time it takes the flame to spread on each of the five specimens. If it is less than four seconds for a raised-surface sample, or 3.5 seconds for a plain surface sample, five additional samples must be tested and the average time of flame spread for all ten, or for as many of them as burn, is calculated. The fabric’s ultimate classification is based on the lower value of the two results obtained from the pre- and post-refurbishment tests.

READ MORE: Consumer Safety, Standards, and the CPSIA

ASTM’s test method for flammability of apparel textiles (D1230) is quite similar to the one prescribed in 1610, which is not surprising since ASTM International members contributed to the development of the federal standard. One difference is that under D1230, fabric samples are dried in an oven for 30 minutes and then placed in a desiccator for an additional 15 minutes prior to testing.

However, despite the many elements shared by the two test methods, it is important to point out that D1230 may not be used for acceptance testing of commercial textile apparel materials. CPSC regulations require that such materials meet the 1610 standard. The ASTM method does provide a quicker, less expensive option companies can use for their own research and product-development activities. And some fabrics that meet certain fabric weight or fiber compositions do not need to be tested to show compliance with the federal mandatory flammability requirements specified in 16 CFR part 1610.

New Equipment and Regulations

One reason this standard is once again under scrutiny is as simple as looking at a calendar. ASTM International standards are to be reviewed on a five-year cycle, and D1230 was last revised in 2017. To have the next version ready for approval and adoption by 2022, the subcommittee is getting things rolling now.

Adding impetus to this routinely scheduled process has been a CPSC request to update the current 1610 test method. “This request is part of a standard review but also addresses the need to update the standard for new laundering equipment used by consumers, new solvents for dry cleaning, laundering procedures, and possible exemptions within the standard,” says Roaldi. “Basically, it is being reviewed to make it current with the latest consumer practices.”

John Crocker is chair of the D13 committee on textiles. He’s also business development manager for SDL Atlas, a global provider of textile testing, quality control, and laboratory equipment. “Modern laundering devices and conditions have changed dramatically from those that were chosen and approved by the committees a number of years ago due to regulations imposed by the EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency] and the U.S. Department of Energy,” he says. “Temperature settings, agitation speed and style, spin speed, and wash and spin times have all seen changes over the years. While some changes seem less significant than others, the net result has been a moving target when trying to settle on what results are correct from one instrument to the next.”

Another change that will likely impact any revisions to D1230 concerns perchloroethylene, one of the most commonly used solvents in the dry-cleaning industry. “Perc,” as it is known, is already due to be phased out in California by 2023, and the EPA has ruled that dry cleaners located in residential buildings must stop using perc machines by the end of this year. Some states are offering financial and technical assistance to shop owners to help them find less toxic alternatives.

“The move from perchloroethylene is being driven by the EPA and is warranted based on its carcinogenic potential,” Crocker explains. “The downside of this is that there is a lot of emerging green technology that the committees just don’t know that much about. The cleaning industry needs to standardize a process so that the labeling and testing community can develop standards that will replicate what the consumer is doing.”

Standards developed by the committee on textiles help make children's costumes safer.

Children and Fire

It is important to realize that the millions of children running around in capes and princess dresses on October 31 are typically not thinking about safety. This is why it is so important to minimize the possibility that anything could go wrong.

And things do, unfortunately, go wrong on occasion. According to the CPSC, there were at least 16 cases in the United States involving costume-related burn injuries of children under the age of 15 between 1980 and 2003, including one death. Eight of the victims were seven or younger, with another five in the 8- to 12-year-old range.

“Children walking down the street — they have these loose, flowing costumes, and they don’t pay attention to whether there’s a candle lit along the sidewalk. Or they might come in contact with a jack-o-lantern that may have a burning candle,” notes Roaldi. “They’re often not sure what to do and panic when exposed to a flame source and ignition occurs. In some cases, they will hide, thinking if they do not see a flame, they are protected.”

The fabrics found in costumes are only part of the issue. “Even though they may comply from a base fabric perspective, with costumes, there are added components that can cause the item to be more flammable,” Roaldi points out. “For example, glued-on glitter or foam attached to the product. Manufacturers have to be very aware that these products should be tested with the components if they’re an add-on; something that may be glued on or layered. Essentially, the product with add-on components and decorations is a different item with different flammability characteristics. They should not just test the base layer at the initial sourcing time for the fabric but go beyond that and test it to be more representative of the finished product.”

The hard work necessary to bring 16 CFR part 1610 and D1230 into closer alignment with the realities of the current marketplace is just getting under way. But the commitment of every stakeholder to ensuring that Halloween costumes, and all clothing items, are safe has been firmly established.

“The various standards committees of the world do their best to develop methods that will adequately represent what the customer may see in the field,” says Crocker. “Customers rarely know all of the details that surround their purchase, but ultimately, it goes all the way back to the original fabric manufacturer meeting a product specification. They need to know how to manufacture the material to meet the end-use performance. If something slips through the cracks, failures can ensue. This is why standards exist: to ensure that a product meets the end use.” ■

Jack Maxwell is a freelance writer based in Westmont, New Jersey.

SN Home

SN Home Archive

Archive Advertisers

Advertisers Masthead

Masthead RateCard

RateCard Subscribe

Subscribe Email Editor

Email Editor