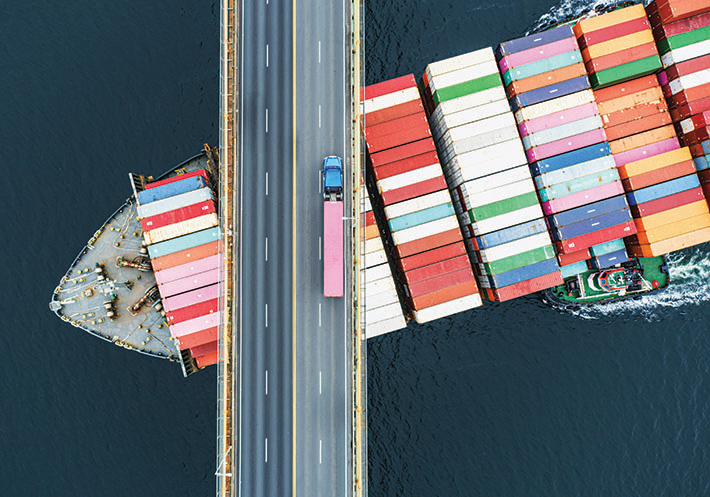

Stronger Supply Chains

The supply chain is comprised of numerous complex interrelationships among manufacturers, shipping companies, container ports, terminals, trucking firms, and more. Traditionally, these elements have been of interest primarily to those tasked with keeping the supplies moving, while the average consumer buying a new television didn’t pay much attention.

That all changed in 2020 with the arrival of COVID-19. A massive pandemic-driven surge in online purchasing by people confined to their homes created unusually high demand for electronics, household items, office supplies, and other products. Meanwhile, on the supply side, manufacturers and their transportation partners grappled with a flood of sick workers and logistical challenges due to this unprecedented confluence of events.

The result? Lengthy delivery delays, unhappy consumers, frustrated business owners — and greater awareness among the general public of the importance of an optimized supply chain.

Increased scrutiny of supply-chain issues was also the impetus behind the formation of a new ASTM International committee on digital information in the supply chain (F49), whose scope is defined as “the formulation of definitions and terminology, and development of recommended practices and guides related to the sharing and use of digital information about the supply chain.” Committee members are taking a unique approach to the task at hand.

Broken Connections

“Everything in the supply chain ecosystem is connected.”

This simple statement from Jeff Weiss speaks to the complex nature of any attempt to improve supply-chain efficiency. Weiss is an attorney with the business law firm Steptoe and Johnson and leads its supply chain team. He is also one of the founding members of F49 — a committee so new officers were being selected at press time — and a leader of the SCORe coalition (more on that to come).

READ MORE: Good Things for Packages

“I think this really started with COVID,” he says. “Everyone was sitting at home ordering stuff online, so you had a lot of shipments coming in from China. Then you had a lot of empty containers going back to China to load up with more stuff, creating a big imbalance between imports and exports as well as congestion at the ports. You also had agricultural exporters trying to get their products to customers overseas, and they couldn’t get their cargo on a ship.”

The domino effect of this logistics bottleneck was profound. Truckers trying to pick up or drop off containers were delayed while they waited for ships idling offshore to dock. Too many containers being offloaded at the same time made it harder to ship goods out, because all the available space at the terminal was occupied by containers on the way in. Eventually, this also created a shortage of warehouse space, with retailers unequipped to handle the higher-than-normal influx.

“The problem is that, from a physical perspective, it’s like ten lanes going into five,” Weiss explains. “There’s not enough infrastructure to handle all those containers, especially in a crisis. The best way to effectively increase capacity would be to communicate really well within the supply chain, so that you don’t have any wasted movements.”

That sounds good, but the crisis revealed an unfortunate truth. Issues in supply chain information sharing had been simmering for years, with each stakeholder trying to address them from within their own silo. Standards were developed and systems were created, but numerous communication problems still remained unresolved.

The crux of the issue is that while every supply-chain actor wants more data, many do not want to share any of their own data. Supply-chain managers want as much information as possible to make good decisions. But they want to share as little as possible of their information with everybody else, afraid to lose a competitive advantage. With everyone acting this way, information that could improve supply chain efficiency is not being shared.

Keeping SCORe

March 2022 was an important milestone in the quest for solutions to these problems. That’s when a meeting jointly sponsored by two organizations involved in the effort was held in Long Beach, California. One sponsor was ASTM. The other was the Supply Chain Optimization and Resilience (SCORe) Coalition, for which Weiss serves as lead counsel.

SCORe, which came together in January 2022, encompasses a broad cross section of key supply-chain players, including major U.S. ports like Los Angeles and Long Beach; providers of technology and engineering solutions; and a variety of trade associations that represent cargo owners (the companies whose cargo is being transported aboard container ships), including chemical producers, health industry manufacturers and distributors, convenience stores, retailers, makers of safety equipment, major consumer brands, and dairy-foods producers.

The March meeting was convened to determine whether there was consensus around creating a new technical committee on the sharing and use of digital information in the supply chain. The ASTM Board subsequently decided to endorse the formation of F49 in October 2022. That initial meeting also helped to establish relationships among the many stakeholders interested in finding ways to improve information sharing along the length of the supply chain. It set the stage for an “event storm” held last November as well.

A Thousand Sticky Notes

Event storming is a workshop method borrowed from software design, in which participants map out a process using sticky notes. The November event storm brought together many different elements of the supply-chain ecosystem to examine a very specific problem: delays in getting containers from ships onto trucks, and how data sharing — or more accurately, the lack thereof — impacts this process.

“We divided into four groups, and we made sure that every group had different skill sets: one cargo owner, one person with a port background, one person with a trucking background, one person with a freight-forwarding background,” says Weiss. “We went through four different virtual rooms: ocean, port/terminal, landside, and retail distribution. Given that everything in the supply chain is connected, we need our standards to cover all modes of that chain.”

Along the way, the humble sticky note played a crucial role. Different colors were used to designate different things, with each step in a particular string of events getting its own note. For example, in the port environment, there was a note for the ship pulling into the terminal, a note for the container being lifted from the ship onto the terminal, and notes for the container either moving to on-dock rail or onto a truck.

“You map out all the different steps,” Weiss explains, “and then, at each step, people could say, ‘It doesn’t always work like that, here’s an exception.’ So there’s a different sticky note for that. There’s a sticky note for ‘I have a standard solution for that.’ There’s a sticky note for ‘I have a technology solution for that.’ There’s a sticky note for ‘Here’s a problem I’ve encountered at this step that we need to solve.’”

The crux of the issue is that while every supply chain actor wants more data, many do not want to share any of their own data.

The crux of the issue is that while every supply chain actor wants more data, many do not want to share any of their own data.

The idea was to establish a shared understanding among all the different supply-chain players of what the events were and what some of the pain points were. The process was also used to determine what standards and technology solutions might already be in place. This helped to avoid duplication and ensure that any new solutions were compatible with existing systems and technologies as well as globally applicable.

The ultimate goal? To uncover some of the initial use cases the committee might want to tackle, as well fostering a spirit of cooperation and collaboration among the various stakeholders. “Once we figure out the nature of the problem — the data that needs to be transmitted, who has it, who needs it, the reasons why it’s not being communicated — we can define the issue and set about tackling it,” Weiss says.

During the four-hour event storm, Weiss estimates that around 1,000 sticky notes were generated — a multicolored testament to the complexity of the supply chain.

A Three-Step Process

The objective of an event storm is to focus on one specific problem, examined from every conceivable angle. After all, it’s difficult to solve a problem without first understanding it thoroughly.

The event storm, however, is only the first phase of a three-step process the committee will continue to employ going forward. The second is what Weiss refers to as a “hack-a-thon.” “This is where we take a problem identified in the event storm and try to build a solution – standards and technology together,” he says. The first hack-a-thon is scheduled for this spring.

The third phase, interestingly, is the one you might think would come first in a committee formed under the auspices of a standards-development organization like ASTM. “Once we’ve completed an event storm and hack-a-thon dealing with a particular issue set, we can then take the resulting use cases and the solutions and feed them into the ASTM process and say, ‘OK, we need a standard to fill a gap that we’ve collectively identified,’” says Weiss. “So we develop the standard and plug the standard into the framework. Then we rinse and repeat. Eventually we’ll cover the major pain points and have a standards-based framework across the entire supply chain. So if someone creates a new standard or a new system, they can plug in.”

He hopes this three-step approach will help generate momentum and encourage more industry stakeholders to get involved. “Before we sit down as a committee and write a standard, we’re going to have a much better sense of what the priorities are from these preliminary events. We want to get people motivated in different sectors to say: ‘I see what you did there, I see the methodology, here are five more issues we want to solve.’” So we’re trying to get quick wins and show this methodology works. We don’t want an academic exercise. People are just too busy. We want to use the standards to solve real-world problems.”

Implementation and Engagement

Given the complexity of the supply chain, F49 is not likely to run short of problems to address and standards gaps to fill. But SCORe’s Drew Zabrocki believes there is a larger, overarching issue.

“It’s not that we don’t have standards or that we don’t have frameworks,” says Zabrocki, general manager of Semios, an agricultural technology company. “It’s just that implementation and engagement is lacking. That’s the big gap.”

As an example of an implementation-related issue, he cites the findings of an initiative of the International Fresh Produce Association (IFPA), which about seven years ago began working with several large agricultural producers and their partners on a framework for data interoperability. They quickly learned that the digitization of relevant supply-chain data was inconsistent. “We found that we still have sticky notes on the trucks, and people taking pictures of packing slips and texting or emailing them off to their trading partners,” he says, adding that while the digitization issue remains a concern, tremendous strides have been made.

Converting various data formats into digital files is only the beginning. “What we run up against as soon as we digitize is determining how well it works together,” Zabrocki says. And according to Weiss, that’s not very well. “Right now, everyone’s using a different system. In some cases you go on a website, in some cases you’re getting status reports from companies via email. Some things are still being done on paper, and sometimes people are on the phone all day trying to find out what’s going on with their container. The data is out there, but it’s often siloed. Even if it’s not siloed, it may not be interoperable.”

FOR YOU: Big Data and Robotics

And the thorny question of interoperability is inextricably linked to another, even more fraught concept: data sovereignty.

Data Sovereignty

“Digitization is the first challenge,” says Zabrocki. “Once you get there you have another challenge: You have to make this stuff work. You need interoperability. But let’s say that’s taken care of. The next challenge is how do you deal with the sovereignty of your information? This data is very valuable, not just to my business but to my trading partners and ultimately to the consumer and the industry as a whole.”

But data out of context can be damaging, and sharing it can backfire. “When you’re in the supply chain, you’re now introducing the concept of trading partners, buyers and sellers, and now that money conversation comes back in,” Zabrocki notes.

He offers the example of farmers who want to demonstrate the sustainability of their operations. They can cite data points from their farm-management systems to buttress the claim.

But within the certification information they provide to the buyer are commercial attributes that could be used by that buyer to put downward pressure on the price, or to negotiate more favorable terms because the buyer has been able to ascertain the farmer’s sales volume or quantity of trading partners.

To eliminate this issue, “The committee will build a framework that can be used to connect with existing standards and existing business systems to enable people to selectively share information for purpose, in a way that everyone can trust, even without accessing the data itself,” Zabrocki says. “Until we address that challenge, interoperability isn’t going to do us any good, and digitization isn’t going to get a return on investment because it’s not being used. So that’s what we’re going to tackle.”

Weiss emphasizes the need to design rules for the exchange and use of data to address the sovereignty issue, noting that the rules are probably going to differ based on the particular problem being addressed. He also points out that there are already many standards and systems in use that F49 intends to leverage so as not to reinvent the wheel.

“Part of our job is to figure out where there’s a gap that requires a new standard, and when it’s a situation where we have all the standards we need but they’re not being used because of the trust issue,” he says. “What we’re going to try to do is create an interoperable framework, where everyone can plug in, within which all the existing standards and systems can interact. The last thing we want to do is to try to create a new system and force everyone to use it. We’re going to create an ecosystem in F49 to build trust and bring people together to solve these issues collaboratively.

It’s a combination of standards development and technology.”■

Jack Maxwell is a freelance writer based in Westmont, NJ.

SN Home

SN Home Archive

Archive Advertisers

Advertisers Masthead

Masthead RateCard

RateCard Subscribe

Subscribe Email Editor

Email Editor